Posted: December 30, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Concussions, Youth Sports | Tags: Concussions, Safety Tag, Youth Sports |

The passage of youth-concussion laws led to a massive increase in medical treatment for concussions in recent years, but other factors also contributed to the trend, suggests a study published online in JAMA Pediatrics last week.

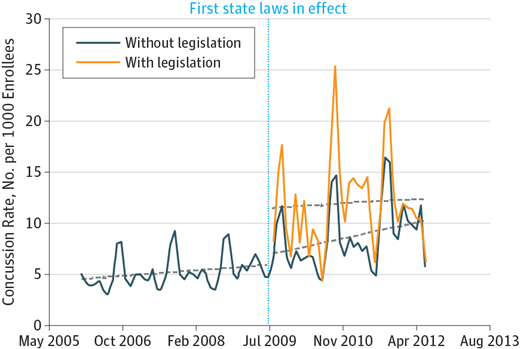

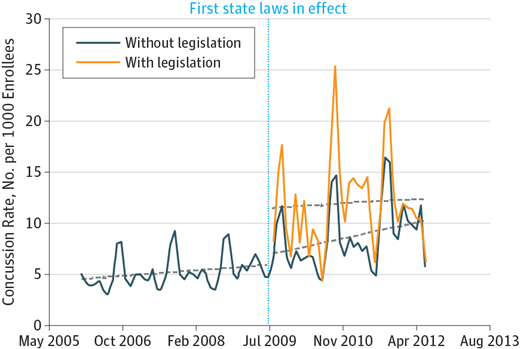

The study examined health-care utilization rates for concussions from Jan. 1, 2006, through June 30, 2012, in states with and without youth-concussion laws. The authors sought to compare the rates of treatment in states with and without such laws to determine how much of an effect the legislation had.

By the end of the 2011-12 school year—the end of the study period—35 states and the District of Columbia had youth-concussion laws on the books. (The other 15 states have since followed suit.) Among insured children between the ages of 12 and 18, 7.15 per 1,000 were treated for concussions in the 2008-09 school year, the last year before the passage of the nation’s first youth-concussion law (in Washington state). In 2009-10, the rate of treated concussions rose to 8.49 per 1,000 children, and then jumped to 10.64 per 1,000 in 2010-11 and 13.27 per 1,000 in 2011-12.

According to the study, rates of treated concussion among children in that age group were rising by 9 percent annually before the enactment of the nation’s first youth-concussion law. After 2009, states without laws experienced a 20.9 percent annual increase in treated concussion rates, and states with laws had an average of 13.1 percent higher rate of treated concussions than states without laws.

Here’s a year-by-year look at the average rate of diagnosed concussions per 1,000 health-care enrollees in states with and without youth-concussion laws in effect:

Overall, states with youth-concussion legislation experienced a 92 percent increase in health-care utilization for concussions between 2008-09 and 2011-12 among children ages 12-18. States without such laws experienced a 75 percent rise in that same time frame, according to the study.

“We estimate that slightly more than half (60 percent) the increase in states without laws in effect resulted from the continued trend of increase in health-care utilization established before the first law was passed,” the authors conclude. “The sources leading to the remaining 40 percent increase in utilization above the prelegislative trend were not evaluated, but it is not unreasonable to believe that general media coverage of laws from other states and/or the injury in general played a role.”

The authors cited a LexisNexis search of news articles from 2006 through 2012, noting articles containing the search terms “sports” AND “concussion” AND “athlete” experienced a six-fold increase during that time.

“There are two stories here,” said Steven Broglio, the study’s senior author and an associate professor at the University of Michigan School of Kinesiology and director of the NeuroSport Research Laboratory, in a statement. “First, the legislation works. The other story is that broad awareness of an injury has an equally important effect. We found large increases in states without legislation, showing that just general knowledge plays a huge part.”

Image via JAMA Pediatrics.

Source: Toporek, Bryan. “Youth-Concussion Laws Led to Massive Increase in Concussion Treatment.” Education Week. N.p., 29 Dec. 2014. Web. 30 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 29, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Concussions, High School, Lawsuit, Youth Sports | Tags: Concussions, lawsuit, Safety Tag, Youth Sports |

BY JON STYF and MIKE DeFABO

Former Notre Dame College Prep football player Daniel Bukal filed a class-action lawsuit against the Illinois High School Association over concussions protocol and management. Sports editor Jon Styf and sports reporter Mike DeFabo discuss.

DeFabo: If you haven’t been following this lawsuit, you definitely should be. To sum it up briefly, the suit alleges the IHSA “does not mandate specific guidelines or rules on managing student-athlete concussions and head injuries and fails to mandate the removal of athletes who have appeared to suffer in practice.” The interesting aspect about this lawsuit is that Bukal, a 29-year-old former player who says he still experiences dizziness and headaches, doesn’t seek damages like some of the NFL suits. He’s not trying to cash in, but just wants baseline testing and medical staff with concussion training at games. What are your views?

Styf: First of all, you’re way off if you think the NFL suits are about “trying to cash in.” Former players want to be able to pay for medical treatment related to a multitude of ailments from their playing days. Beyond that, on the high school level, something needs to be done. If you’re going to have kids playing a dangerous sports like that, you need someone on the sideline who can handle a head injury situation (i.e. medical staff) and they need to have the right data (i.e. baseline test) to do it the right way. If youth football leagues can mandate it, why is the IHSA so hesitant? It’s about money. The IHSA said that handling it in the courts isn’t the best course of action, but how many other times have they said that while they would be sued over policy? The organizations and their members don’t want to be told how to run their schools and teams. But, there is a real head injury issue both here and throughout the country in all sports. The time has come to deal with that appropriately.

DeFabo: IHSA Executive Director Marty Hickman said in a news conference that if the lawsuit is successful it could “eliminate some programs in Illinois.” He essentially said football will only exist in the wealthy school districts. I’m not buying that argument. Bukal’s attorney, Joseph J. Siprut, had the perfect response in Joey Kaufman’s story earlier this week. “The IHSA’s claim that our firm’s concussion class action could result in the demise of high school football, or create a system of “haves, have nots” (those that have football and those that don’t) is a cheap and cowardly tactic designed to engender opposition to the lawsuit,” Siprut wrote. “Put simply, the IHSA is trying to pass off this logic: ‘If you like football, then you should oppose this lawsuit!’ They might as well have said: ‘If you like cute puppies, then you should oppose this lawsuit!'”

Styf: If you like your kids, you should like this lawsuit. It’s one thing to choose football as a profession, knowing the risks, and play in the NFL. It’s a completely different thing to be a high school player and head back onto the field after a concussion and risk your life for the game because no one was there to check you out properly after a hit. This isn’t a perfect solution, no solution can make football completely safe. But it’s about limiting the risk, which is largest when a first concussion isn’t diagnosed. As USA Today pointed out in November, eight high school football players died last year in injuries directly related to football. That’s real. And the point of that story is, why does it happen in high school and not in college and the NFL? One explanation is that there are a ton more high school games than those on higher levels. Another explanation could be that there is much closer management of head injuries on the higher levels.

Source: Styf, John, and Mike Defabo. “Take 2: Concussion Lawsuit against IHSA to Have Deep Impact.” Northwest Herald. N.p., 27 Dec. 2014. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 29, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Asthma | Tags: asthma, chronic illness, Safety Tag |

By Dr. ANTHONY L. KOMAROFF

Asthma is a complicated and serious disease. It can behave differently from hour to hour and from day to day. A person with asthma needs a plan for what to do at each stage of the disease. I’ll describe the elements of the plan in a minute, but first a little background on asthma itself.

Asthma assaults the lung’s airways. The airways are the tubes through which the air you breathe enters and leaves your lungs. During an asthma attack, the airways get narrower as the muscles surrounding them constrict. The airways also become inflamed, and mucus fills the narrowed passageways. As a result, the flow of air is partially or completely blocked.

A mild asthma attack may cause wheezing, difficulty breathing or a persistent cough. Symptoms of a more severe attack can include extreme shortness of breath, chest tightness, flared nostrils and pursed lips.

Two types of medications are used to treat asthma: controllers and relievers. Controllers - usually inhaled corticosteroids - are medicines taken regularly to reduce the likelihood of asthma attacks. They reduce inflammation, which decreases mucus production and reduces tightening of airway muscles.

Relievers, or “rescue” medications, are used just during asthma attacks. They stop or reduce the severity of the attack by relaxing the muscles around the airways to improve airflow. Bronchodilators are often used as rescue medications.

Everyone with asthma should have an asthma action plan. This is a written plan that details what you need to do to control your asthma. It also explains what to do when you experience asthma symptoms or in case of an emergency. You may feel that you already know this information, but when you or a loved one is struggling to breathe, it helps to have a set of written instructions to refer to.

Asthma action plans are often divided into “zones.” You should be able to tell what zone your son is in from his symptoms. The action plan will tell you what you need to do in each zone. For example:

- GREEN ZONE: Doing well. No coughing, wheezing, chest tightness or shortness of breath; can do all usual activities. Take prescribed long-term controller medicine.

- YELLOW ZONE: Getting worse. Coughing, wheezing, chest tightness or shortness of breath; waking at night; can do some, but not all, usual activities. Add quick-relief medicine.

- RED ZONE: Medical alert! Very short of breath; quick-relief medicines don’t help; cannot do usual activities; symptoms no better after 24 hours in yellow zone. Get medical help now.

People live with asthma for many years and come to know a lot about it. So a written asthma action plan may seem unnecessary. But in my experience, people who suddenly get sick sometimes forget to take the steps they know they should. A written asthma action plan can be a valuable reminder at a moment of trouble.

Source: Komaroff, Anthony L. “Asthma Action Plan Will Help during an Emergency.” Coeur D’Alene Press. N.p., 28 Dec. 2014. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 26, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Concussions, High School, Lawsuit, Youth Sports | Tags: Concussions, high school sports, lawsuit, player safety, Youth Sports |

By MICHAEL TARM

CHICAGO (AP) — A former high school quarterback followed in the steps of one-time pro and college players Saturday by suing a sports governing body — in this case the Illinois High School Association — saying it didn’t do enough to protect him from concussions when he played and still doesn’t do enough to protect current players.

The lawsuit, filed in Cook County Circuit Cook on the same day Illinois wrapped up its last high school football championship games, is the first instance in which legal action has been taken for former high school players as a whole against a group responsible for overseeing prep sports in a state. Such litigation could snowball, as similar suits targeting associations in other states are planned.

The lead plaintiff in the lawsuit is Daniel Bukal, a star quarterback at Notre Dame College Prep in Niles from 1999 to 2003. He received multiple concussions playing at the suburban Chicago school and, a decade on, still suffers frequent migraines and has experienced notable memory loss, according to the 51-page suit. Bukal didn’t play beyond high school.

The IHSA did not have concussion protocols in place, putting Bukal and other high school players at risk, and those protocols remain deficient, the lawsuit alleges. It calls on the Bloomington-based IHSA to tighten its rules and regulations regarding head injuries at the 800 high schools it oversees. It does not seek specific monetary damages.

“In Illinois high school football, responsibility — and, ultimately, fault — for the historically poor management of concussions begins with the IHSA,” the lawsuit states. It calls high school concussions “an epidemic” and says the “most important battle being waged on high school football fields … is the battle for the health and lives of” young players.

Bukal’s Chicago-based attorney Joseph Siprut, who filed a similar lawsuit against the NCAA in 2011, provided an advance copy of the new lawsuit to The Associated Press. The college sports governing body agreed this year to settle the NCAA lawsuit, including by committing $70 million for a medical monitoring program to test athletes for brain trauma. The deal is still awaiting approval by a federal judge in Chicago.

The IHSA lawsuit seeks similar medical monitoring of Illinois high school football players, though it doesn’t spell out how such a program would operate. It contends new regulations should include mandatory baseline testing of all players before each season starts to help determine the severity of any concussion during the season.

An IHSA spokesman had no immediate comment on the lawsuit.

The lawsuit only targets the Illinois association. High school football isn’t overseen by a single national body equivalent to the NCAA, but rather by school boards, state law and 50 separate high school associations. Siprut says he intends to file suits against other state governing bodies.

Washington was the first state to pass laws addressing sports concussions in children in 2009, including by barring concussed players from going back into the same game. All 50 states have now adopted such laws.

But the new lawsuit alleges respective governing bodies, like the IHSA, have had patchy, insufficient implementation of various state mandates.

Around 140,000 out of nearly 8 million high school athletes have concussions every year, most of them football players, according to the NFHS. Some estimates put the number of concussions much higher, in part because many go unreported.

Eight high school students died directly from playing football in 2013 — six from head and two from neck injuries — while there were none last year in college, professional or semi-professional football, according to a 2014 report by National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research.

Speaking Saturday after the filing, Siprut said the legal action wasn’t intended to undermine high school football or America’s most popular sport as a whole.

“This is not a threat or attack on football,” he said. “Football is in danger in Illinois and other states — especially at the high school level — because of how dangerous it is. If football does not change internally, it will die. The talent well will dry up as parents keep kids out of the sport— and that’s how a sport dies.”

Source: Tarm, Michael. “High School Head Injury Lawsuit Filed.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 30 Nov. 2014. Web. 26 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 18, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Volunteer, Youth Sports | Tags: Volunteer, Youth Sports |

By ASHLEY ROTEN

Athens’ number of young athletes and athletic programs is steadily growing, as well as the need for youth sports coaches.

Along with parents and teachers, coaches help influence and shape a young person’s life and motivate a healthier lifestyle.

If you know a thing or two about sports, why not step forward and be a volunteer coach for the youngsters of Athens?

The Athens-Clarke County Leisure Services is seeking volunteer coaches for youth basketball and youth soccer. Although these are the only two opportunities in need at this time, as spring approaches, more programs will begin and more coaches will be needed.

Coaches are expected to instill the love of the sport and comradery amongst players over winning.

A coach should empower their players through education and positive feedback.

Even if you’re not athletic, you can still volunteer. Experience is not necessary for coaching and training will be provided. All volunteers must pass a criminal background screening, be 18 years or older, commit to a an entire season and dedicate up to three hours per week to practice and game time.

Source: Roten, Ashley. “Do One Thing: Volunteer as a Youth Sports Coach.” Online Athens. N.p., 17 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 17, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Uncategorized |

By Jamie Hale

PANAMA CITY BEACH- A sport that’s getting a lot of attention for its injuries may surprise you.

According to the Center for Injury Research and Policy, soccer players have more concussions than wrestling, baseball, basketball and female softball players combined.

Girls soccer ranks second for the most concussions in high school sports.

Soccer players use their heads to often hit the ball. This move is called a “header.”

“When you go up to do a header, you try to use your hands and get the people away from you, so you don’t hit heads with them or don’t collide with the goal keeper,” said college soccer player Emily Vogler.

Experts say forbidding headers in soccer is one way to prevent injuries.

This isn’t the exact reason for most concussions, but the long-term contact between head and ball over time could cause brain damage.

Source: Hale, Jamie. “Soccer Players Among Highest Concussion Rates.” WJHG RSS. N.p., 16 Dec. 2014. Web. 17 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 10, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Youth Sports | Tags: basketball, player safety, Youth Sports |

By ADAM REILLY

Jack Woods has been playing basketball since he was a little kid. But three years ago, he got serious, joining a highly competitive travel program led by Eric Polli. Now, Polli said, Woods is a player to be reckoned with.

“You want someone to score? He can score,” Polli said of the 14-year-old shooting guard. “He can shoot. He can attack the basket. He is the definition of a scorer.”

Woods practices with his Mass Elite squad at least once a week after school and spends many of his Saturdays playing in tournaments around the state. Ask him if the commitment has been worth it, and his answer is unequivocal.

“It’s improved my game a lot,” Woods said. “My shooting improved tremendously, because of one of the coaches that helped me with my shot and stuff. I went from probably one of the worst shooters to one of the best.”

For Woods, who said he models his game after Miami Heat star Dwayne Wade, early dedication to one sport seems to be working out. But some skeptics contend that for society at large, it’s a troubling trend.

“When I first started doing this in 1992, in basketball, it was fairly rare around here to see a sixth-grade travel basketball team,” said former NBA player Bob Bigelow, who’s made a second career arguing against over-intense youth sports. “Now, a lot of these communities have fourth-grade travel teams.”

Bigelow, who grew up in Winchester and played collegiately at the University of Pennsylvania for legendary coach Chuck Daly, argues that too many kids are pushed to take sports too seriously at too young an age.

“Why are we organizing teams?” he said. “Why do we have adults coaching kids when they’re 7?”

“The pure, simple fact of the matter is something I’ve been saying for 25 years,” Bigelow added. “Your athletic ability prior to puberty is meaningless as an indicator of your athletic ability post puberty.”

As Bigelow notes, there’s also a clinical argument to be made against going too hard too young. According to the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, excessive early training and competition can cause a variety of injuries, as well as psychological burnout. But Bigelow believes there’s a deeper problem.

“Adults want to win; kids want to play,” he said. “That’s the difference.The more adult needs you add to these sports, the more adult vision, the more adult needs have to be met.”

Still, despite warnings from Bigelow and other critics, the professionalization of youth sports marches on. Case in point: the Boston-based startup CoachUp, which connects aspiring athletes with professional coaches for sessions that cost an average of $50 per hour.

“Thirty to 40 million kids across this country play youth sports,” said Jordan Fliegel, CoachUp’s founder and CEO. “And they’re passionate about it.”

Fliegel got private coaching for basketball after his freshman year in high school, at Cambridge Rindge and Latin. He recalls it as a life-changing experience, one that helped determine both his athletic and his professional future.

“I couldn’t shoot at all, could barely dribble,” Fliegel said. “I got a private coach that summer, and sophomore year, I was the starting center on the varsity team.”

Later, Fliegel attended Bowdoin College in Maine, where he went from being a benchwarmer as a freshman to the team captain and MVP as a senior. (That year, he proudly notes, the Polar Bears enjoyed their best men’s basketball season in school history.) After college, he played professionally in Israel with Hapoel Jerusalem.

If Fliegel’s story is inspirational, it also makes it tempting to see CoachUp as part of the broader youth-sports arms race. But Fliegel has a different, more reassuring take.

“We believe anyone who has dream should be supported, and that some athletes and some people bloom late,” he said. “Sometimes it takes a long time. And if you’re passionate about something, you should be able to pursue it.”

Which, of course, is exactly what Jack Woods is doing with basketball. Ask Woods about his goals, and his answer is refreshingly modest.

“I hope to take it to the highest level I can: hopefully go to college and play for a good college, stuff like that,” he said.

Asked if he imagines going to a major college program, or to a smaller school like Bowdoin, Woods splits the difference.

“Something in between,” Woods said. “I don’t need anything major. I just want to be good.”

And that’s an ambition that’s difficult to fault.

Source: Reilly, Adam. “The Youth-Sports Conundrum: How Intense Is Too Intense?”WGBH News. N.p., 2 Dec. 2014. Web. 10 Dec. 2014.

Posted: December 3, 2014 | Author: admin | Filed under: Concussions, Youth Sports | Tags: Concussions, Safety Tag, TBI, Youth Sports |

By Mark Prigg

The study was presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

‘This study adds to the growing body of evidence that a season of play in a contact sport can affect the brain in the absence of clinical findings,’ said Christopher Whitlow at Wake Forest School of Medicine, who led the study.

A number of reports have emerged in recent years about the potential effects playing youth sports may have on developing brains.

However, most of these studies have looked at brain changes as a result of concussion.

Dr. Whitlow and colleagues set out to determine if head impacts acquired over a season of high school football produce white matter changes in the brain in the absence of clinically diagnosed concussion.

The researchers studied 24 high school football players between the ages of 16 and 18.

For all games and practices, players were monitored with Head Impact Telemetry System (HITs) helmet-mounted accelerometers, which are used in youth and collegiate football to assess the frequency and severity of helmet impacts.

Risk-weighted cumulative exposure was computed from the HITs data, representing the risk of concussion over the course of the season.

This data, along with total impacts, were used to categorize the players into one of two groups: heavy hitters or light hitters.

There were nine heavy hitters and 15 light hitters.

None of the players experienced concussion during the season.

All players underwent pre- and post-season evaluation with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) of the brain.

DTI is an advanced MRI technique, which identifies microstructural changes in the brain’s white matter.

The brain’s white matter is composed of millions of nerve fibers called axons that act like communication cables connecting various regions of the brain.

Diffusion tensor imaging produces a measurement, called fractional anisotropy (FA), of the movement of water molecules along axons.

In healthy white matter, the direction of water movement is fairly uniform and measures high in fractional anisotropy.

When water movement is more random, fractional anisotropy values decrease, suggesting microstructural abnormalities.

The results showed that both groups demonstrated global increases of FA over time, likely reflecting effects of brain development.

However, the heavy-hitter group showed statistically significant areas of decreased FA post-season in specific areas of the brain, including the splenium of the corpus callosum and deep white matter tracts.

‘Our study found that players experiencing greater levels of head impacts have more FA loss compared to players with lower impact exposure,’ Dr. Whitlow said.

‘Similar brain MRI changes have been previously associated with mild traumatic brain injury. However, it is unclear whether or not these effects will be associated with any negative long-term consequences.’

Dr. Whitlow cautions that these findings are preliminary, and more study needs to be done.

Source: Prigg, Mark For. “High School Football Can Damage the Brain in Just ONE Season - Even If Players Never Suffer a Concussion, Study Finds.”Mail Online. Associated Newspapers, 02 Dec. 2014. Web. 03 Dec. 2014.

Recent Comments